A fallen tree lay across the Situk River in Alaska, half the trunk above the surface, its branches raking the rushing water, the other half below. Big John pulled hard on the oars to slow his cataraft from sliding into the deadly strainer. He needed to make a decision quickly. He could try to float over the submerged section of the tree and risk getting hung up. Or he could sharply turn the cataraft sideways and clear the tree completely. The thought of flipping sideways and falling into the icy water set him and he decided to shoot for the submerged half.

It would be all or nothing — ganbatte, as the Japanese call it.

In Alaska, everything is bigger, bears and moose, and the danger deadly, but Big John’s confidence would never waver, not here, not ever. He floated past the downed tree and was already spying the next spot where steelhead migrating from the ocean could be taken with his rod and reel. He’d come all this way from the San Francisco Bay Area with a few close friends and was intent on being the top fisherman on this year’s trip, whatever that meant.

He found a promising slot and beached his cataraft on the far bank. There were still patches of snow on the ground and his body had a deep chill, which made him shiver. He wore waders, a warm jacket, cotton shirt, thermal underwear, wool socks, and still he could not feel his feet. But when Big John hooked a fish on his first cast in the slot, he suddenly felt warm again. He fished more than a half-dozen holes this day, catching and releasing more steelhead than he could recall without his fish counter. Alone on the last frontier, he began to whistle and sing about raindrops falling on his head. Crying’s not for me.

The Situk River ran full of fish, and Big John could feel the backs of them bumping his cataraft in the darkness.

The sun was going down on this first day of a two-day float. Big John took out his flashlight from the saddle bag to search for the pullout where he would spend the night inside a decrepit cabin. To miss the pullout would be a mistake. He turned on the flashlight now and again to check for a sandy bank that marked the pullout and listened intently to the water for signs of trouble, like fallen trees and big boulders. But there were none, and the Situk River ran full of fish, and Big John could feel the backs of them bumping his cataraft in the darkness. He was calm when others would be anxious.

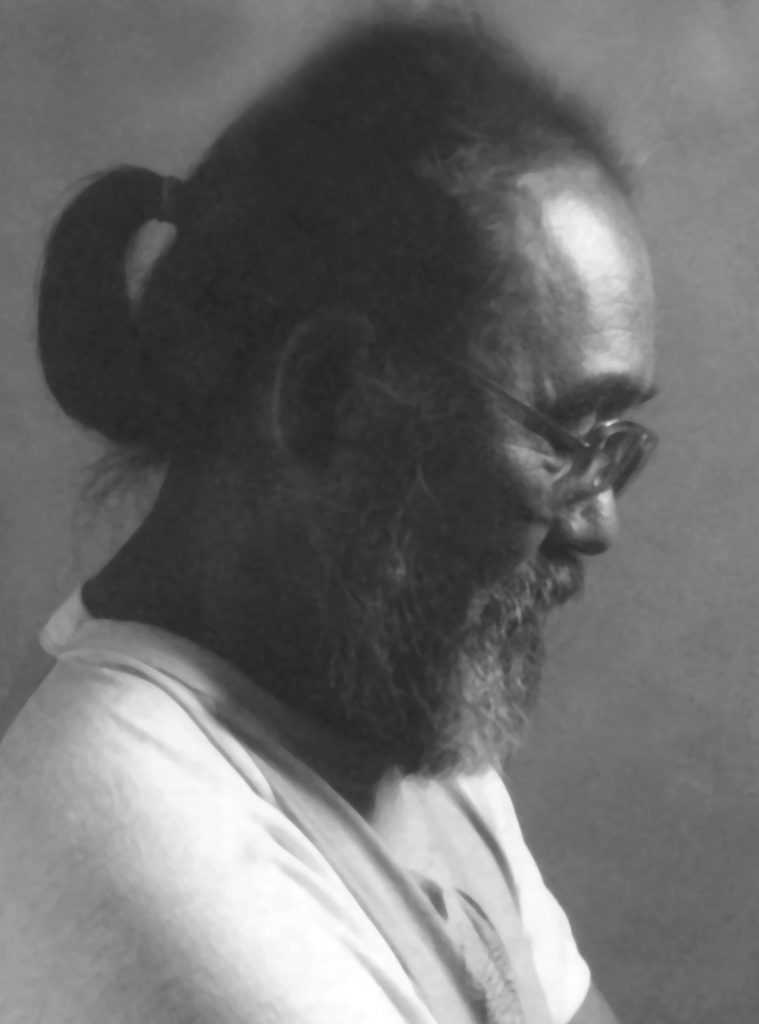

Then Big John spotted the pullout, landed on the sandy bank, and tied his cataraft to a tree for the night. He didn’t climb the hill to the cabin but waited for his friends, his flashlight a beacon to guide their way. Always have your friend’s back more than your own, he told me. One by one, they landed at the sandy bank and tied off their catarafts like horses. There was Rick and Paul and then his best friend, the Old Fisherman, who was almost always the first one out, the last to come in, his fish counter high in the double digits.

They climbed the hill together.

At the cabin, the foursome went about their work, firing up the portable heater, preparing dinner, reloading fishing vests, their familiarity with each other meant few words were spoken. Some smoked cigars and drank whiskey. Soon the little cabin filled with the snores of tired men. Did Big John dream? I don’t know. Perhaps he dreamt of fishing: a shared cabin near the Mattole River for winter-run steelhead; a black bear stalking a hillside at the Eel River campsite; a bonfire started by the Old Fisherman and Little John, blazing away only a stone’s throw from the Trinity River; a riffle made of steelhead that had been trapped in the Kalama River after Mount St. Helens erupted; and always of a Dodge blue van chasing adventure and finding it.

The blue van had ranged hundreds of thousands of miles searching for steelhead but also carrying Big John, his wife and four children to Yellowstone, Little Big Horn, Snake River, Crater Lake, Grand Canyon and other wild places. His wife enjoyed most of all reading books while lying on a homemade bed inside the blue van, which he had built out of wooden boards and stitched cushions. Big John was known for his hot temper and lifelong passion for fast cars, winning drag races in his youth, so it was strange to see him overcome with melancholy when, finally, a tow truck hauled his blue van away.

When Big John woke, the Old Fisherman was already in his waders and raring to go. Rick and Paul were gearing up quickly in a silent race. Big John never rushed for anything. He knew it was going to take all day to fish and float to the river’s mouth where, with any luck, there would be a school of spirited steelhead just in on the evening tide. It would be here where Big John, with his fiercely competitive nature, would make his bid for top rod. He owed much to the spirit of competition. It was competition that drove him to start his own company. It was competition that he instilled in his children. It was competition, or just plain stubbornness, that helped him survive among people who reminded him daily they didn’t want japs in their communities.

The days would grow darker, his health would fade, his beloved wife would pass away.

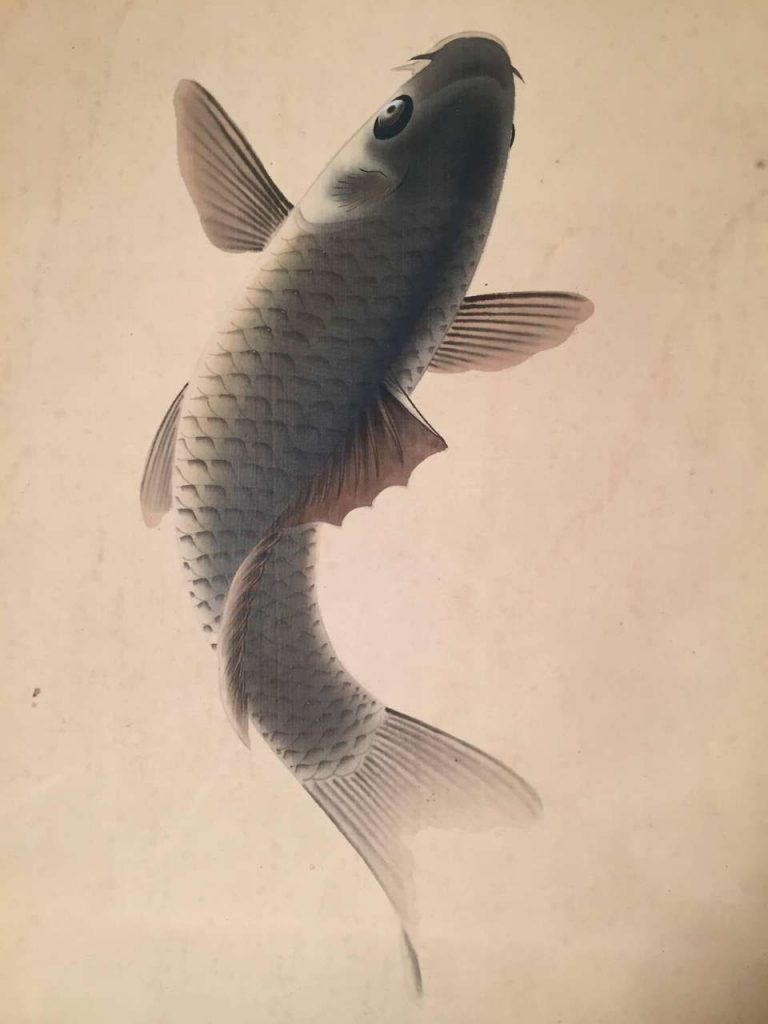

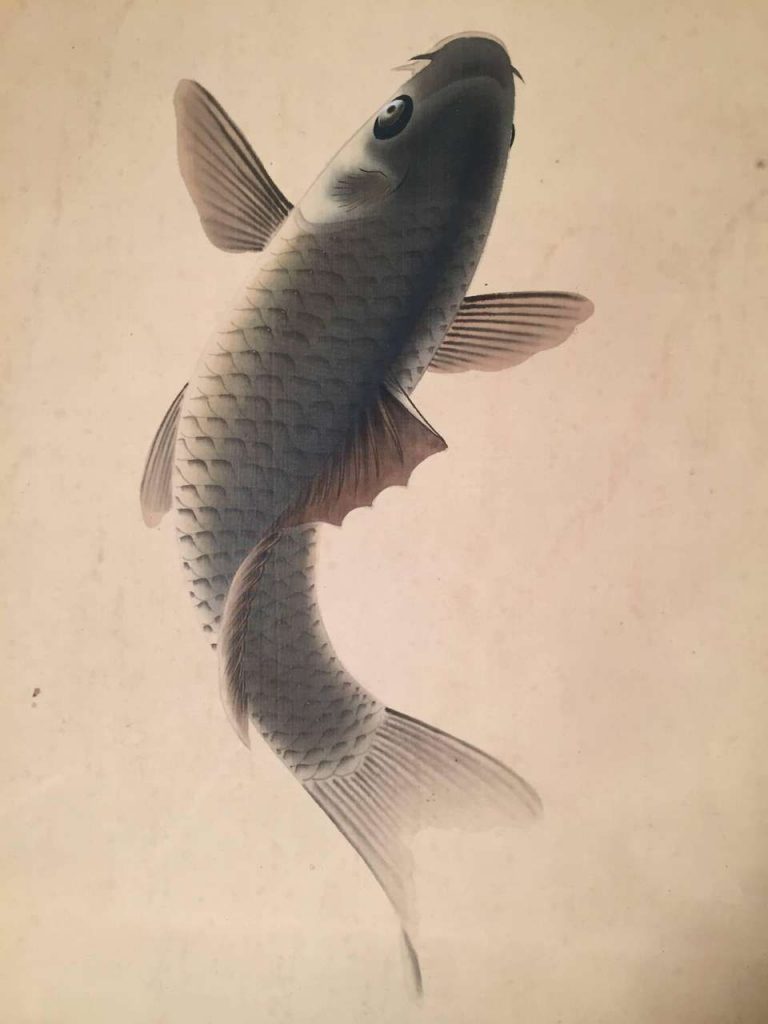

The long day added to the fish counter, maybe three steelhead at the Confluence Hole, one or two at every other stop. At last they arrived at the Tidewater Hole, a long stretch of blue-ribbon water near the mouth of the river. The sun was still up and Big John had on his polarized glasses and he looked into the water and that’s when he saw it — a dark mass of torpedo shapes moving as one heartbeat.

His eyes widened, hands trembled, and he made his first cast.

All the men lost fish after fish after fish, their reels dumping line, clickers sounding like a buzz roll on a snare drum, and hooks failing to hold porpoising steelhead. Even the Old Fisherman could not add to his fish counter. These were the hottest fish Big John had ever seen, and he thought, if only I could land one.

The sun was now dipping below the treetops. Not much time left. The days would grow darker, his health would fade, his beloved wife would pass away. But now was the moment, right now was the moment to live, to be alive, and a leviathan took his offering and he set the hook as hard as he could. The great fish ran upstream. It leaped out of the water, a silhouette in the setting sun, turned and charged, its life force seemingly limitless. Yet the hook stayed pinned and Big John held on.

The light was nearly gone and the weight of the fish grew heavier. Exhaustion had crept into his soul, as his wife used to say. But he would not quit this fish. This time would be different. It would be all or nothing. The fish’s will broke and it came to him and he landed it on the bank, this bank and shoal of time. Big John, the strong one, struggled to lift the steelhead and show his friends, but his smile meant more to them.

And the Old Fisherman hugged him.